The Dangerous Dogs Act 1991 - what is it?

On 12 August 1991, the Dangerous Dogs Act came into force, banning four types of dog.

We were told it would prevent dog attacks, but more than thirty years on, injuries caused to humans by dogs are at an all-time high and pet dogs are killed every month simply because of how they look.

Section one of the Dangerous Dogs Act (1991) outlaws five types of dog:

- pitbull terrier

- Japanese tosa

- dogo Argentino

- fila Brasilerio

- American XL bully (added 2023)

The law makes it illegal to own, sell, breed, give away or abandon one of these types of dog.

This is often referred to as ‘breed specific legislation’, or ‘BSL’, but actually the law doesn’t recognise a dog’s family tree, or pedigree.

Instead, UK legislation bases the decision on whether a dog is illegal on looks alone – a dog’s breed, a dog’s parents’ breeds, DNA testing and behaviour don’t come into it.

Classing a dog as illegal based on looks alone means that half of the puppies in a litter of crossbreeds could be illegal types, while the other half of the litter is legal types.

The Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) has given guidance to law enforcers on what to look for when ‘typing’ a dog. Pitbull terrier types are defined using measurements based on an American breed standard for show dogs from the 1970s. Enforcers use a tape measure for this test.

No information has ever been issued to enforcers about how to identify the three other banned types by the UK government.

Guidance has been given for XL bully type dogs, but this can be easily applied to many bulldog breeds, including staffies and crosses.

Under the law, a dog that looks like an illegal type can be seized and killed based on looks alone – the dog doesn’t have to have behaved aggressively or injured anyone.

When looks could automatically kill

Up until 1997, being born to look like one of these types signalled an automatic death sentence for these dogs – even if they had never shown any aggressive behaviour. Death was mandatory. Looks could literally kill.

An amendment to the law that year meant that dogs who were found guilty of looking like a banned type could be ‘exempted’ if they passed a court behavioural assessment and proved they could live happily and peacefully in the community.

Jo-Rosie is a dog behaviourist and works as an expert independent witness for the courts in Dangerous Dogs Act cases. She also had personal experience of the exemption process, having been through it with her own dog, Archie.

Jo-Rosie and Archie’s story

“He is the most affectionate dog I’ve ever had. He’d get under your skin if he could,” says Jo-Rosie Haffenden of her beloved pet Archie. “He loves to snuggle up at night and just wants to puts his paws around you.

“But I once had a guy shout at me in a train station, ‘You shouldn’t have that type of dog, they’re dangerous’, which was quite intimidating.”

Eight-year-old Archie is a pitbull type. Under the eyes of the law, his looks make him ‘dangerous’, but in reality he is no more a threat to society than any other dog of any other breed. Despite suffering unimaginable cruelty in his past, Archie has a wonderful temperament, is well trained, and has a devoted and responsible owner who loves him and makes sure he is a well-adjusted member of society – just as she does with her other three dogs, none of whom are illegal types.

Jo-Rosie explains: “Just like any other dog believed to be of an illegal type, Archie was measured by the dog legislation officer. They come to your home and take about 60 measurements using a tape measure. If a substantial amount of these measurements meet the American breed show standard, the dog is a pitbull type.

“The number of measurements is open to interpretation, but case law suggests if 60 per cent of the measurements meet the standard then the dog is of type. There is no standard set of measurements on which to benchmark the other three banned types; it is open to interpretation."

“The process of taking the measurements is incredibly intrusive for the dog,” says Jo-Rosie. “You have to measure things like the circumference of the bottom of the back leg, from the nose to the tip, from the tip to the top.

"All of these measurements are taken by a stranger who the dog has never met before. A lot of dogs take umbrage to this, and this can cause lots of problems.”

The Dangerous Dogs Act is often cited by lawmakers as an excellent example of how not to enact legislation. It passed through the Houses of Commons and Lords much more quickly than legislation usually does, and is considered by legal experts to have moved through too fast to be subject to the normal levels of scrutiny.

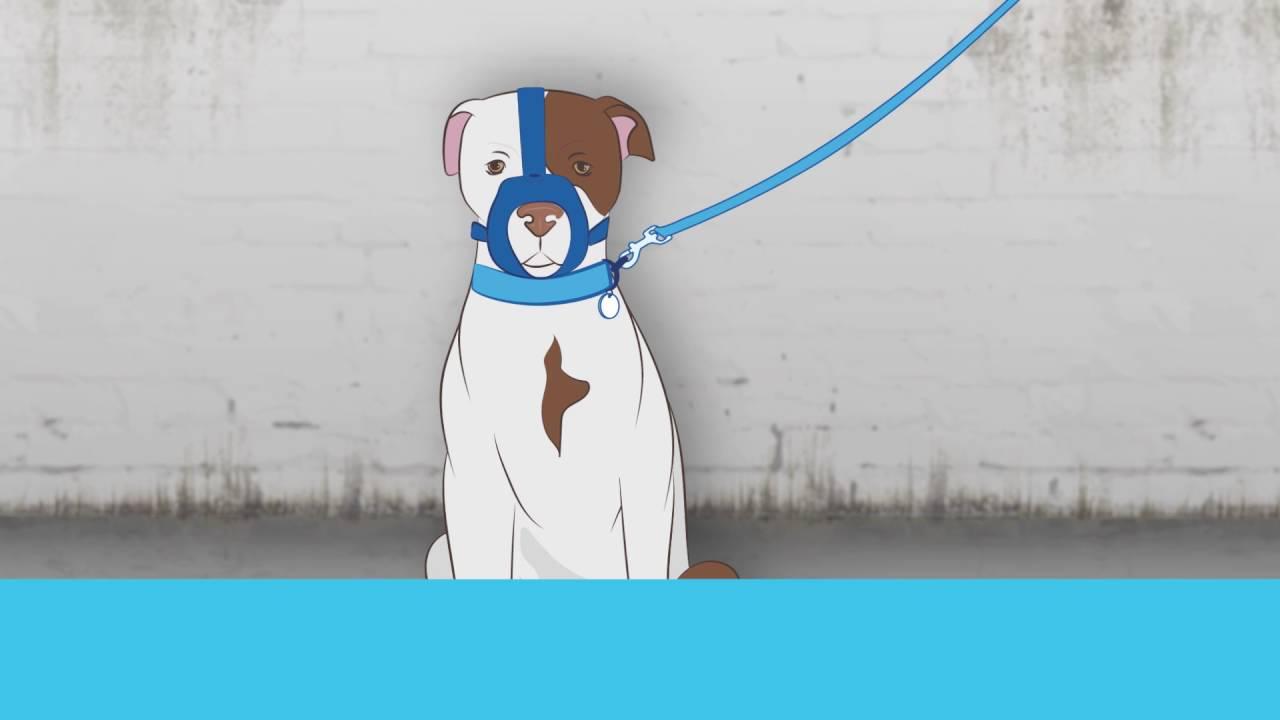

[Above: Archie must be muzzled in a public place. He loves going for walks with his friend Ella. Ella doesn't have to wear a muzzle, even though Archie is the one of the two of them who has proved he is well-behaved in the courts.]

Jo-Rosie says that this means court cases can be long and drawn out with arguments over tiny details: “I’ve been in court before where we’ve spent over an hour arguing over one measurement.

"Think about how ridiculous that is; we’re basically saying the dog is dangerous if the circumference of one part of his leg is over 5.7 millimetres, and if it isn’t, then he’s not dangerous. That’s what it came down to in that case. And when you look at that part of a dog’s leg, you realise that there’s a lot of give, so when you’re putting a tape measure around it you can make it pretty much whatever you want it to be.”

Living within the law

Dogs who prove to the court that they are not a danger to the public are added to the Index of Exempted Dogs. They are allowed to return home under certain conditions, including that they are neutered, kept on a lead and muzzled in a public place.

They must wear a muzzle even when travelling in a car, as this counts as a public place.

Owners must keep the local authority up to date with where they live at all times. When Jo-Rosie moved house recently, she had a visit from the dog legislation officer with 30 minutes of letting them know she had moved.

Although Archie had already passed the court behavioural assessment and his owner had kept up to date with all the paperwork, his measurements were taken again.

For a dog who has just moved to a new environment, to have a stranger come into your personal space can be a bit much. But Archie is a soppy thing, and he’s used to it by now.

“On a logistical basis for a normal person with an illegal type as a pet, it’s incredibly difficult,” says Jo-Rosie.

Archie must also be insured for public liability under the terms of his exemption. Failure to keep up with this could lead to him being euthanised. It's also impossible for illegal types to get health insurance – no UK pet insurance company will insure them – leading to hefty bills if your dog becomes sick.

[Above: Archie's favourite thing to do is enjoy a Kong while snuggling up on the sofa. It's a dog's life!]

All this for dogs who are the only canines ever to have passed a state behavioural assessment. No other dogs who are right now enjoying an off-lead run though woodlands or playing a retrieving game in a field, have had to pass such a test, and they live life without these restrictions.

Time for change

Becky Thwaites, Blue Cross Head of Public Affairs, said: “Many dogs that are seized as illegal breeds are in fact well-behaved dogs with responsible owners, who just have the misfortune to have the wrong measurements. Nearly as many dogs - not banned breeds - were seized under section 3 of the Dangerous Dogs Act as under section 1 last year for being dangerously out of control, highlighting how important it is for government to change the legislative focus from what a dog looks like to dealing with irresponsible owners of any breed of dog to keep our communities safe.”

Sadly, many of those dogs would have been kept away from their owners in kennels for the duration of a costly court case, before being allowed to return home.

Blue Cross wants to see an end to legislation that singles out dogs based on looks alone and the focus switched to prevention, and we’re continuing to work with the Minister for Environment and Defra, to ask them to repeal the unfair and ineffective law.

Becky added: “We need a piece of specific dog control legislation, enabling enforcers to step in and take action before dog attacks happen, as well as sufficient resources and training to allow them to do so.”